First Look: DT's New F535 One Fork

List your favourite suspension manufacturers. The chances are that if you are here on Pinkbike, DT Swiss are not high on that list, if they are there at all. It's not that they are new to suspension, they have been making forks and shocks for the best part of 20 years now, and in 2008 they bought the UK's Pace suspension to reinforce their lineup, but how successful their suspension line has been since then depends on your perspective.

If you are an XC racer looking for a fork that needs tying to a rock on windy days, then DT are definitely right up there. Nino Schurter and Jenny Risveds piloted their OPM Race 100 fork to Olympic gold in Rio 2016. Dig beyond that headline and the racing palmarés for the OPM line are even more

If you are an XC racer looking for a fork that needs tying to a rock on windy days, then DT are definitely right up there. Nino Schurter and Jenny Risveds piloted their OPM Race 100 fork to Olympic gold in Rio 2016. Dig beyond that headline and the racing palmarés for the OPM line are even more

F535 ONE Details

• Travel: 130, 140, 150, 160mm

• Wheel size: 27.5" or 29"

• Position-sensitive damping

• Lineair spring with Coilpair

• Offsets: 44mm (27.5"), 51mm (29")

• Weight: 2,020 - 2,090g

• Hub/axle: Boost 15x110mm

• Price: €1,149 EUR / $1,551 USD

• Intended use: AM/enduro/ebike

• Available: Now

• www.dtswiss.com

• Travel: 130, 140, 150, 160mm

• Wheel size: 27.5" or 29"

• Position-sensitive damping

• Lineair spring with Coilpair

• Offsets: 44mm (27.5"), 51mm (29")

• Weight: 2,020 - 2,090g

• Hub/axle: Boost 15x110mm

• Price: €1,149 EUR / $1,551 USD

• Intended use: AM/enduro/ebike

• Available: Now

• www.dtswiss.com

Their head of marketing, Friso Lorscheider, admits that "nobody was waiting for a longer-travel fork from DT." That put them in a very unique position, with no outside pressure they were free to design their F535 from the ground up, starting with what they call a white paper. On that white paper they listed what they believe a modern all-mountain fork should do. Their analysis should not surprise you. When they started work on this fork back in 2015, they identified three things that a fork needs to offer: sensitivity at the start of the stroke, support in the mid-stroke and progression at the end. That sounds familiar, right? While every suspension company is touting those qualities, there is a strong case that DT are the first to actually offer all three in a single package.

The Big Difference

To understand why the F535 is different you need to start with how every other suspension fork works. The damper controls the fork's action by regulating the oil flow, using a precise series of ports to determine the behaviour of the fork; from this we get high- and low- speed compression derived from the speed at which the oil passes through the ports. The problem here is that we have just one variable to try and provide two outcomes and despite what the press releases may tell us, while you only have one variable you are always going to have to make a trade-off between sensitivity and mid-stroke support. That is why racers' bikes tend to feel so firm, they will prioritise the support part of the equation at near-total exclusion of sensitivity.

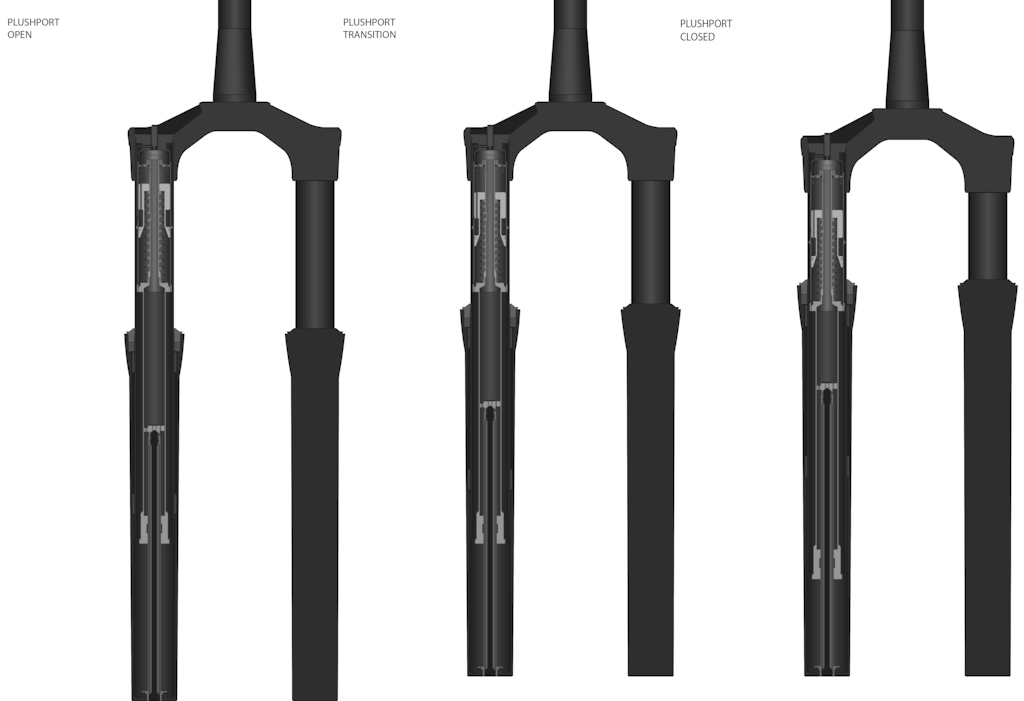

At the moment, this is the only graphic we have from DT about how the Plushport works as the technology in the fork is still patent pending and they say they do not want to talk in more depth about this at the present. It's not entirely clear from the graphic, but the basic idea is that the amount of compression damping increases depending on where the fork is in its travel. From 0-30% travel it's fully open, after which it increases gradually up until 50% travel is reached, at which point the highest level of damping has been reached.

The F535 adds a second variable - another port that works in a very different way, DT calls it Plushport. At 0-30% travel this port is wide open, diverting oil away from the main damping circuit, meaning the oil can flow freely and the fork's movement is virtually undamped. Once you reach 30% travel the movement of the fork begins to close the port gradually, reaching fully closed at 50% travel. For that 20% of the stroke you have a gradually increasing amount of compression damping as the port diverts more oil through the damper, with the theory being that the transition should be seamless. Finally from 50% onwards the port is fully closed and all the oil is flowing through the damper, which offers a very high level of compression damping to provide that all-important mid-stroke support. Essentially you can have two very different levels of compression damping within a single fork and, if DT have got it right, it will all work seamlessly together to offer the holy trinity of fork performance: sensitivity, support and progression.

Chassis and Air Spring

While the damper may be very impressive on paper, it is worth zero if the rest of the fork around it is no good. First up is the chassis. Before DT started work on this fork they did their homework - they conducted extensive testing on a range of forks from their soon-to-be competitors to work out what they liked and what they didn't. One of the big initial steps for them was jumping to a 35mm stanchion - in the past DT had made nothing bigger than 32mm, but after running their old 32mm-stanchioned fork with a prototype damper against its more modern rivals they quickly realised that if they wanted to compete they needed something bigger.

With the size set they then began fine-tuning the stiffness. They made a conscious decision to offer a more compliant chassis; they felt that one of their top competitors in the enduro fork market was actually too stiff, to the detriment of the overall bike handling. However, when looking at the weight of the fork it is important not to conflate stiffness with strength. While this fork may not be the stiffest fork on the market it's not lacking in strength - it's rated for a combined system weight of 150kg. To put that in context: they believe that a 130kg rider could happily strap one of these to the front of his 20kg e-bike and ride safely (most forks have a total system rating of 120kg).

To design the air spring they again started with a blank piece of paper and tried a number of different solutions before settling on their final configuration. One idea they tested extensively was a dual chamber air spring - much like Ohlins are using on their high-end forks. However, after much evaluation their lead engineer, Sam Zbinden, admits that, "There is only a small benefit with this system, and we decided that it's not worth the additional weight, the additional costs and the additional complexity for the customer, therefore we didn't go for this solution."

What they went for is a fairly standard, large-volume air spring, but they paired it with something unique - a small coil for the initial stroke. Using the large air chambers they could keep the mid-stroke fairly linear, with the traditional air spring ramp up at the end of the stroke. To get around the initial stiction that is a characteristic of all air springs, they have dropped in a tiny, very light coil spring at the start of the stroke that can start the fork moving, then handing over duties to the main air spring.

To design the air spring they again started with a blank piece of paper and tried a number of different solutions before settling on their final configuration. One idea they tested extensively was a dual chamber air spring - much like Ohlins are using on their high-end forks. However, after much evaluation their lead engineer, Sam Zbinden, admits that, "There is only a small benefit with this system, and we decided that it's not worth the additional weight, the additional costs and the additional complexity for the customer, therefore we didn't go for this solution."

What they went for is a fairly standard, large-volume air spring, but they paired it with something unique - a small coil for the initial stroke. Using the large air chambers they could keep the mid-stroke fairly linear, with the traditional air spring ramp up at the end of the stroke. To get around the initial stiction that is a characteristic of all air springs, they have dropped in a tiny, very light coil spring at the start of the stroke that can start the fork moving, then handing over duties to the main air spring.

The Final Package

With the beating heart of the fork set, next up are the aesthetics. This fork is discrete. While I was running the fork unbadged at home I started talking in depth to a passing German rider at the end of a trail who wanted to know about how my bike was working. We chatted for a good 10 minutes and throughout he never so much as glanced at my fork, despite it being the only one outside DT at the time. But, if you look at it next to any of the current crop of 160mm forks it is unique in its own way - the design language is boxier but clean, with aluminium caps covering the valves and adjusters at the top of each leg. The best analogy for this fork is when a manufacturer releases an updated version of an existing car - at first the new design looks a bit weird, unusual even, but after a little while you realise that you have got used to it and the previous version now looks dated. The covered adjusters are no accident or oversight - DT do not want you fiddling with this fork too much, so they have made a conscious choice to make it less easy for you (more about this in the Setup section).

(Clockwise from the top-left) The top covers that pop off with a T10 key on the remote version; the axle handle pulls off to reveal the all-important T10 key; talk about attention to detail, even the top cap covers are etched so you know which side each one belongs to; the compression adjuster for the remote version of the fork - it too needs the T10 to make adjustments; the compression adjust for the non-remote version, you'll never guess what size torx key you need to adjust it - plus the ergonomically wonderful lockout lever; the recessed rebound adjuster that needs the T10 to even reach it - the message on this fork is clear, DT don't want you spending too much time playing with the dials on this fork. That said, it's almost a shame you don't need to use the adjusters as the indexing is so crisp and sharp it's hard not to make a Swiss watch pun.

The axle is a simple screw-in affair with a T10 tool hidden inside, which fits every bolt and adjuster on the fork so you can fix most minor irritations trailside. There is an integrated mudguard, which begs me to ask why more people haven't made them before? It is such a clean, simple solution and looks far classier than a piece of plastic zip-tied to your €1,000 fork.

Setup

DT have opted for a very clean-looking integrated hose guide and mudguard, unfortunately setting these up is a pain in the ass. Both use tiny T10 bolts from the back to hold them in place, they are fiddly and it is hard to get to them to tighten. Fortunately, the hose guide only needs doing as often as you change brakes and I personally tend to leave mudguard on all year round - certainly, when they are as slick and good-looking as this one I see no reason to pop it off, I'll take those extra grams all year. Speaking to DT about this, they acknowledge that this element is not 100% right and I would expect to see some clever little revisions sneak into production not too far down the line.

Setup for riding may be one of the biggest challenges this fork faces - not that it is not utterly simple to do so (it is), but that some riders may not trust the way DT have designed the F535. After all, most of us have spent our entire riding lives fiddling with and fettling our suspension. Whether it is something as simple as trying different pressures or clicks of compression and rebound, all the way up to playing with shim stacks and springs, we have all done this to some extent for as long as we have ridden bikes, so to be asked to forget all that is, well, worrying. Once you get your hand around the knowledge that most of that fettling is to fine-tune the sensitivity/support compromise to your personal taste and that you don't need to make that compromise with this fork, then it makes a lot more sense. DT provide a handy chart that gives you a precise air pressure for your weight and how many clicks of rebound you should run. As for compression? Just leave it wide open. That is it. Go ride.

(Clockwise from the top-left) The integrated mudguard, the hose guide, a rear view of the fiddly mounting bolts and the cap that covers the non-axle side of the dropout - a very clean, little touch.

Talking to their engineers they recommended using a digital pump, but for my first few rides I didn't have one to hand and with a little attention you can get the pressures close enough for the fork to work fine. In fact, having later switched to a digital pump I don't think it is quite as critical as DT say it is (they are Swiss, after all). You do have the option to add or remove volume reducer tokens in the air chamber, but it came with two out of a possible three fitted and I never reached a point with this fork where I felt like I needed more or less progression. If you are partial to a good car park test of your suspension, the chances are that the speed of the rebound on this fork will worry you. It is fast, properly fast, but again, you need to trust that DT got their sums right and go ride the fork before you start fiddling.

Two rides in I couldn't resist and tried going nuts, adding a single click of compression. On the first descent of the day I felt there was a moment where the fork didn't completely compensate for my piss-poor cornering technique as the bike slid around on wet, loose rock, so I added a click of compression. After one more descent I took it back off again. It is hard to explain the feeling, it is not that the fork didn't work with more compression, but it added a weird quality to the movement of the fork. In short - DT have the settings nailed and if you can get your head around it, this is the simplest fork to set up and go riding with I have used this side of a Kona Project Two.

For my first ride on the F535 I had an hour or so grinding out the kilometres to the trailhead for one of my favourite trails. After an intensive day of talking to DT about the fork earlier in the week, my head was full of questions and worries, to the point where I had massively over-thought the whole thing before I ever reached dirt. The good news is that when you get up to speed and switch off those unnecessary mental processes this fork doesn't give you much to think about, in the same way that you don't worry if gravity is going to be there or not. Quite simply, it gets on with its job in a way that lets you focus completely on the trail and how you want to ride it in a way no other fork I have ever used does.

The two different versions of this fork tested: 160mm and 130mm (both 29).

Breaking down its trail manners we need to start at the beginning of the stroke. This fork is supple, so supple that my 11kg Scott Spark will sag under its own weight standing. The small coil at the base of the air shaft does its job marvelously, giving a small amount of stiction-free travel then handing over to the lightly damped initial part of the air-spring stroke. What is most impressive is how seamless it all is - you simply don't feel a transition, just an incredble suppleness. If you were riding this fork blind you would not guess that it was a two-stage spring.

Then we get to that initial part of the air-sprung stroke and it is basically undamped, with complete focus on traction and comfort. It certainly does a great job of cutting out trail chatter and keeping your hands fresh for the whole run - on a ten-minute track more suited to enduro bikes, I could hit it flat-out on my 120mm Spark and reach the bottom with my hands still fresh. Part of the reason I chose that first trail is that it tends to get quite dry and dusty and there are some sketchy insides and blown-out off-cambers that you need all the available traction to hold - the F535 made it feel easy. There is a small trade-off here, in that if you are going to have it that open, then you cannot expect it to offer immediate support under braking loads and you will blow straight through the first portion of the travel if you are ham-fisted enough, which does give a very minor diving sensation, but it is tiny and you quickly reach the next part of the stroke which is designed to deal with just that.

The mid-to-end-stroke provides dependable support, ramping up nicely towards the end of the travel. As soon as you completely reach the second phase of the damping it is a brute in velvet gloves. I don't think I ever had a harsh moment where I blew through the stroke, the fork always rode nice and high in the stroke, never wallowing or diving. Checking the travel indicator at the end of a run I would consistently find that I had used pretty much all the travel, but never quite all of it and I could not tell you where on the trail I got closest to the bottom. One thing I have always found is that when a fork holds its composure well, you feel less hurried as you ride, like you have more time to see the trail and make your decisions about where and how you want to ride. The F535 certainly does that and with all that traction you can start to hunt for new ways of riding sections. It is here that the initial context is important - this fork provides support and progression on a par with the most aggressively damped forks I have used. Yet, thanks to that supple initial stroke it never felt unforgiving or hard, it just always felt like enough fork for the job. I did most of my testing with a 130mm fork and with suspension that is both this active and supportive, I think it could lead many people to reconsider how much suspension they need to be running.

There is one first with this fork for me - this is the first time in a long time that I have used the lockout lever on a fork. This comes back to the sensitivity/support equation and my personal preference has always landed on the support side. What this meant was that I tend to run enough compression damping on my fork that you simply don't need a lockout. On long, steady climbs I still don't think a lockout is necessary, but when I was tired and the gradient went up I was thankful for the lockout on the F535. Because it is so active at the start of the stroke it provides very little support when your form goes out of the window, so that little lever is a godsend. I'm not a huge fan of their remote lever (I also don't like additional geegaws on my bar), but the version on the fork leg is lovely - it has a very positive feel and shape.

In terms of chassis rigidity, this fork was benchmarked against a Pike during development and that bears out on the trail. This is a good place for DT to be as a super-stiff fork really needs the right frame and wheels to work in combination with it to avoid harsh trail feedback, where a slightly more forgiving fork will combine well with a much wider range of bikes and wheels. The traction from this fork has also made me re-think how much stiffness you need on the trail to some extent. One of my little tests for a fork are rolling endos through corners - a move you tend to need quite often here in the South of France. If you're not familiar, you use the front brake to lift the rear wheel, then you pivot on the front wheel to get through the corner, ideally you do all this while still going as fast as possible. In the past I have tended to prefer a stiff fork for this, it feels solid as you turn around the front wheel. For example, the uber-rigid Marzocchi 350 felt amazing for this (it was the one good thing that fork did). Yet with this fork I didn't find myself missing that stiffness, rather the traction on the front wheel meant the tyre was still biting so you had grip to turn with. It is a more delicate feeling, but once you are used to the slightly different approach it feels great.

I have not put this fork through a structured, timed test, but I have been running it on my home trails since mid-April where I record all my rides on Strava. The timing sheets from my home trails says that running this fork I have been putting in PRs or times very close (within a second over long runs) to my best everywhere, on every trail - that straight out of the box it has me on a par with the highly tuned and fettled fork with the high levels of compression I normally prefer, but it is also the most comfortable and easy-to-live-with fork I have ever used at the same time.

Issues

There are a few things about this fork that we need to talk about. Firstly is travel adjustment. Because of the way the position-sensitive damping works and that the air springs are specific to the travel, if you want to change the travel you will need to change the damper and air spring. That means that once you commit to a certain amount of travel you are committed until you are ready to buy a new damper and spring. Then there is the question of offset and this fork throws into light the question of how important offset is. Quite simply, it was not something on DT's radar when they developed this fork, so you can only get the 27.5 fork in 44mm and the 29 in 51mm. Because DT create the offset in the lowers, you cannot switch crowns to reduce your offset either and the cost of moulds for new lowers mean it may be some wait for a reduced offset version.

There is one final question for a new fork like this: reliability and service. So far I have put in a few hundred km on this fork and it has worked like clockwork. Service intervals are on a par with Fox and Rockshox and part of the reason this fork weighs as much as it does is because of the amount of metal used internally, which is a reassuring sign. Having used DTs wheels for a number of years I am inclined to trust them on this front - more so on discovering that the development for this fork was complete in 2017, but they took another full year to keep testing and picking at the details to get this right. The other advantage they have is their dealer network - because they are so dominant in the spoke market, almost every single bike shop has an account with DT and to support that network DT has built a robust service provision around the world to support their products.

Verdict

Before you think I am getting carried away with this fork, I want to put its performance into context. If you set up a limited test looking into just one aspect of suspension performance, I would lay money that Rockshox or Fox would come out on top. They have had years and millions of dollars of research to reach a point of high refinement with their suspension. Talk to one of their competitors about how hard they are working to even match them, if you do not believe me. If you tune a 36 or a Lyrik for, say, only mid-stroke support, then I could not tell you that the DT is better in that single aspect, although it is to its credit that it is playing in the same league. With a conventional damper you simply cannot have such a free initial stroke paired with such robust support later in the stroke - you have to compromise. The DT F535 is the first fork to ditch that compromise, and it does it utterly seamlessly out on the trail. I think every almost any rider could benefit from this running this fork - for racers and hard-chargers it offers the mid-stroke support to push the limits, but combines that with unprecedented traction and comfort; for absolute novices it offers the ease of use and comfort they need, but combines it with mid-stroke support and progression that they don't yet know they need to help keep things upright when they get it all wrong.

As journalists we have to be careful with our words - we are fed a lot of marketing bullshit and we need to be careful not to regurgitate it blindly. DT have never made any particular claims about this fork (to me, at least) - it is not their way. They wanted to make a "good" fork that you can strap to the front of your bike and go riding without having to think about it. Not only have they done just that, but I think they have gone quite a way further. While the chassis and air spring are good, what they have achieved with the damper in this fork might just be the most important step in suspension performance since we ditched the elastomers.

Author Info:

Must Read This Week

Sign Up for the Pinkbike Newsletter - All the Biggest, Most Interesting Stories in your Inbox

PB Newsletter Signup

One thing in favor of RS and Fox of course is that if you're not 100% happy with what you got, there are still some upgrades available for your forks from the likes of Vorsprung etc. That's one selling point. That these forks may not be perfect out of the box, but you can upgrade your Yari to something quite special.

But won't be able to get me away from MRP from now on... it's just amazing.

MRP, Manitou, and Cane Creek are all on the table at this point.

Sounds to me like the IRT rivals/beats our ramp control - or at least that's the indication I get from many out there. And I like that Manitou is fairly straight forward to rebuild at home. I've not dug into the Helm, but typically CC suspension isn't as easy to self service, and tends to be quite expensive to have done elsewhere.

More research needed on MRP. I have no doubt they are great forks though.

Also, there is the cost factor. I definitely don't mind paying top dollar for something that's clearly the best, but when you're splitting hairs, cost often drives it home for me. And, the Mattoc can be found for pretty reasonable prices, so there is that.

I remember when Manitou invented that in the 90s.

I remember when Manitou invented this, too. My 2010 Minute MRD had MARS, which was exactly this.

position sensitive dampers never did work! Maybe they figured it out?

I was disappointed by my pike the first time i tried a 36. I'm not the only one saying this, and I still see pikes everywhere.

I think EXT use a bottom out cone like avalanche does or fox for their polaris buggy shocks.

youtu.be/PX_CUP5BcTU

Looks like a dope fork though. Don't know if it's 1.5 ribbons, but still looks rad.

"The damper controls the fork's action by regulating the oil flow, it uses a precise series of ports to determine the damping behaviour of the fork based on its speed of movement. From this varying speed of movement we get different high and low speed compression damping behaviour."

Worrying, yes that is the right word.

Call me paranoid but I can't help to see that covering the adjusters may hide a sneaky tendency to make us forget about the good old external adjusters and sell us "plug and play" fork for all, which in my opinion would be a total fallacy.

I personally love to be able to adjust a shit ton of stuff on my fork, if my fork could have more dials than the control board of a spaceship I would take it.

Suspension setup, how it affects the overall performance and feel on the bike is extremely interesting and the more, the finer the adjustments, the better the ride in the end.

I'd say that people thinking that the adjusters on their suspension are gimmicks for nerds which do not translate into a real world difference should start playing more with their knobs.

Off the back of that though, as someone who rides a DT Swiss fork, I can't agree with your assessment of their customer support: "to support that network DT has built a robust service provision around the world to support their products." Their support for other products may be amazing but when it comes to forks, they have pretty much always designed them not to be tampered with by the home mechanic, but unfortunately there are only two places you can send them to for servicing in the UK and both have a bad rap. I tried the one with better reviews, and following a full service on my fork, the fork came back with the one problem fixed, another problem remaining and a new problem that wasn't there before! I would be hesitant to lay down money on their forks in future, although I do love how light weight they are!

I did...but I'm 42. That part made me smile.

Lyrik RC2 and Grip2 26 are about the closest 170 29er forks. Both don't seem to exist in my country. I have to buy a fork then convert it with more parts...

MRP and Formula both make 170mm 650b forks and 160mm 29er forks so the parts are there. They don't seem interested in it.

I'm now looking at the Öhlins DH Race fork @170mm and 46mm offset as I can't get a SC LT 29er fork.

@mattwragg : why make a compression dial, if you have to leave it open all the time ?

DT told me they added it as people prefer to have one - I guess it was kind of reassuring and you're not just "locked out" of the fork.

(joke - I'm loving my Push coil conversion)

Was hoping to see a Selva 29er with sub 46mm offset and 170mm travel. Would be awesome to see the Nero R air spring make its way into the Selva line. I have no use for a lock-out or firm up of the front end.

Yes the fork will dive if you grab the brakes hard.

I'll live with that "trade off" for a plush fork.

Mid stroke support equates to a lack of small numb sensitivity and greater fatigue.

"At 0-30% travel this port is wide open,(...) and the fork's movement is virtually undamped. Once you reach 30% travel the movement of the fork begins to close the port gradually, reaching fully closed at 50% travel. (...) Finally from 50% onwards the port is fully closed (...) which offers a very high level of compression damping to provide that all-important mid-stroke support. Essentially you can have two very different levels of compression damping within a single fork"

Then the air spring adds progression to the spring rate.

Thus keeping the fork from diving.

Everyone else uses damping circuits to achieve mid stroke platform.

This uses position for damping rates.

The author notes a small amount of diving .

The initial stroke has very little damping .

It's the transition from coil to air that gives the mid stroke support.

Fork looks like upgraded version of the Manitou