GT Fury Review

TESTED

GT Fury

WORDS Mike Levy

PHOTOS Bryce Piwek

GT couldn't have written a better script if they tried. After a year of the Atherton siblings racing on the original carbon fiber Fury, with admittedly dated geometry, the company debuted a completely new version of the bike last off-season. Slightly more travel, a revised Independent Drivetrain and, most importantly, drastically evolved geometry that better suits today's racers and tracks. Jump forward a few months and Gee and Rachel have won both of the first two World Cup races of the 2013 season, which has to be the most stunning debut of a new downhill bike to date. While there can be no arguing that GT has left the gate on a flyer, and that their World Cup racers are clearly fond of the new Fury, just how well does the 220mm travel bike perform under riders who don't have the DNA or skill set of the Athertons? Our exclusive test of the new Fury came aboard a bare frame that we assembled with a mix of SRAM, Avid, RockShox, FOX and Spank components, a build kit that had our test bike weighing in at a very respectable 36.9lb. GT will offer four different versions of the Fury, all assembled around the same aluminum frame, that range from $3,099.00 for the Elite model to $8,140 USD for the World Cup build, as well as a frame only option (price to be announced) for those who want to build up their Fury with parts of their choice.

GT Fury Details

• Intended use: Downhill racing

• Rear wheel travel: 220mm/8.6''

• Aluminum front and rear triangles

• Uses revised Independent Drivetrain suspension

• Single pivot suspension w/ stiffening link

• FOX DHX RC4 shock

• Slacker, lower, and longer than previous Fury

• Full length 1.5'' head tube

• 12 x 150mm axle spacing

• ISCG-05 chain guide tabs

• Weight: 36.9lb as tested (as tested)

• Frame weight: 7.72lb (Claimed, w/o shock)

• Availability: Sept/Oct, 2013

• MSRP: $3,099.00 - $8,140 USD

Unconventional Numbers

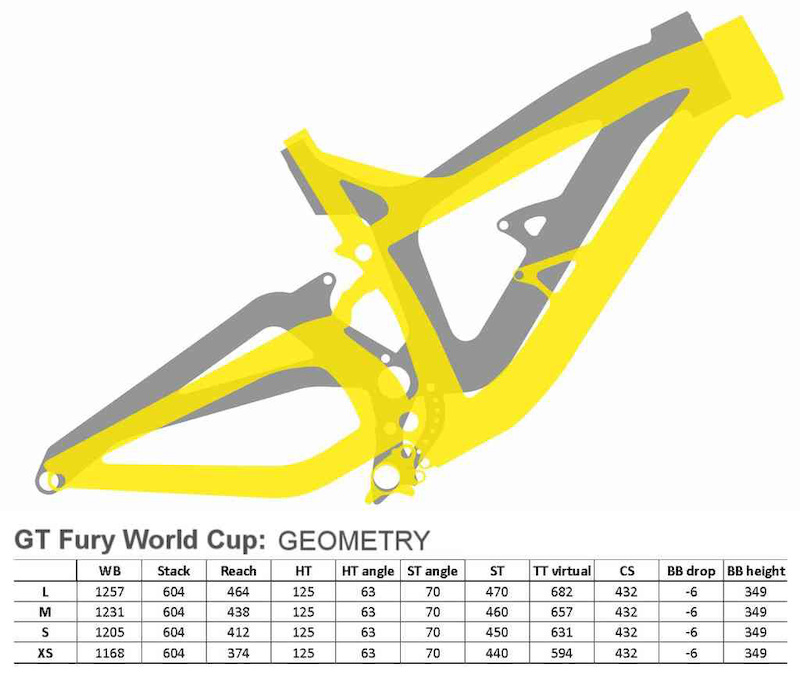

Geometry has moved along quite a ways since the original Fury was designed in 2008/2009, and the old bike's 65° head angle was looking dated, so it comes as no surprise that GT went with a much slacker front end that puts the front wheel further out ahead of the rider, with the bike employing a 63° head angle. What did come as a shock to us, though, was the 657mm top tube length for our medium sized test bike. For reference, a medium Trek Session sits

That long front end makes for an equally long wheelbase, with the bike measuring in at 1231mm overall. That is 50mm longer than the Session and 86mm longer than the V10, all despite the new Fury's rear end being 10mm shorter than the old bike. Again, this fact highlights just how long the front of the bike is compared to some of the competition. The bike's bottom bracket height is also quite low, although at 349mm it isn't the lowest when it comes to production downhill bikes.

Fury Construction Details

There is no carbon to be found on the new Fury frame, with GT choosing to debut an aluminum version of the bike before making the anticipated leap to carbon fiber in the future. Regardless, GT says that the bare frame weighs 300 grams less than the previous carbon version, as well as sporting significantly improved rigidity all around, no doubt a byproduct of the frame's massive aluminum tubing and clever construction. The top tube is large enough in size to look as if it would pass as a down tube on many other bikes, and it drops down sharply from the full length 1.5'' head tube while becoming more ovalized as it nears the seat tube. That same theme continues out back, with GT manufacturing a solid looking swingarm that offers a curiously large amount of tire clearance. The bike's 12 x 150mm axle threads in from the non-drive side, and GT uses pinch bolts on both sides of the swingarm to keep it from shifting in its home.

GT has been clear about their desire to create a chassis that is leaps and bounds stiffer than their previous designs, and they boast about some serious improvements in that department: 26% at the front of the bike and 38% at the bottom bracket. Those are some big numbers, but they are entirely believable given just how burly the frame looks in person. The bike's swingarm uses a massive diameter aluminum pivot axle that turns on equally large sealed bearings, and the swingarm itself is captured within twin spars welded to the down tube and upright junction. The whole arrangement not only looks impressive, it also allows GT to space the main pivot bearings out as widely as possible, adding further stiffness.

The rearward shock mount is also home to a compact linkage, with the shock mounting hardware also acting as the pivot assembly. While it may look like the shock is controlled via the linkage, it is in fact a pair of interconnected links used to arrest lateral movement of the swingarm, without affecting the suspension's action.

The Fury's Independent Drivetrain Suspension Explained

GT has long been known for their I-Drive suspension layout, referred to as 'Independent Drivetrain' on more recent models, that utilizes a ''floating'' bottom bracket unit. This single pivot suspension configuration has been designed to allow for a relatively high main pivot without the drawbacks that are usually associated with it - excessive chain growth. The high pivot helps the bike to swallow up hard, direct impacts thanks to the rearward axle path that it affords, but it is the floating bottom bracket that lets such a design work without the massive chain growth (tugging on the chain as the bike goes through its travel) that would usually be associated with such a layout. GT's Independent Drivetrain does this by letting the bottom bracket move in approximately the same plane as the rear axle by locating it on a separate element that pivots off of the swingarm, all while being attached to the front triangle by a short link, essentially creating a four-bar linkage layout. In the simplest of terms, the bottom bracket moves rearward slightly to mitigate the chain growth of the bike's high pivot. GT's approach has been around for awhile in a few different executions, all having great success on the race circuit, including Gee and Rachel's dominance of the first two World Cup stops of 2013.

How is the Fury's Suspension Different From the Old Design?

While both the new Fury shown here and the previous generation may use a similar looking layout, GT has made some very important changes on this latest iteration. The most obvious distinction between the two is the location of the main pivot, with it positioned much lower on the new bike. GT's Etienne Warnery, the engineer behind the new Fury, told us that this gives the bike ''better pedalling performance when you sprint on rough terrain''. How so? The lower pivot should be less affected by chain tension and therefore stay in contact with the ground instead of losing traction due to it firming up. The other major difference is the much shorter length of the dog bone link, the short connecting rod that ties the floating bottom bracket unit to the front triangle. This small piece determines how much the bottom bracket unit moves as the bike goes through its travel, with it having about 10mm of total motion, and that lowering that figure relative to the old bike was an important byproduct of ''having the force coming from the bottom bracket to the swingarm being directed closer to the main pivot in order to remove its consequences,'' Warnery explains. The new pivot location, the much more compact Independent Drivetrain suspension, and the lower shock position in the front triangle all work together to create a lower center of gravity compared to the previous design.

While both the new Fury shown here and the previous generation may use a similar looking layout, GT has made some very important changes on this latest iteration. The most obvious distinction between the two is the location of the main pivot, with it positioned much lower on the new bike. GT's Etienne Warnery, the engineer behind the new Fury, told us that this gives the bike ''better pedalling performance when you sprint on rough terrain''. How so? The lower pivot should be less affected by chain tension and therefore stay in contact with the ground instead of losing traction due to it firming up. The other major difference is the much shorter length of the dog bone link, the short connecting rod that ties the floating bottom bracket unit to the front triangle. This small piece determines how much the bottom bracket unit moves as the bike goes through its travel, with it having about 10mm of total motion, and that lowering that figure relative to the old bike was an important byproduct of ''having the force coming from the bottom bracket to the swingarm being directed closer to the main pivot in order to remove its consequences,'' Warnery explains. The new pivot location, the much more compact Independent Drivetrain suspension, and the lower shock position in the front triangle all work together to create a lower center of gravity compared to the previous design.

Riding the

Fury

Fury

| While the GT may have felt long and unwieldy when sitting on it at a standstill, it comes alive when dropped into the environment it was intended for: steep, fast, and rough trails. |

Handling: Sitting on the Fury leaves one wondering if the bike will only perform on big-boy tracks or under riders who hold a pro license, but that isn't the case. Somewhat surprisingly, the long GT feels very practicable and surprisingly agile, but without that flightly personality that can plague a downhill bike with a relatively short wheelbase. Getting the bike around tight corners wasn't an issue whatsoever, so long as the speeds didn't dip down too low or the terrain didn't level out, and we found ourselves actually carrying more momentum through sharp direction changes than on shorter bikes, possibly because the long front end allowed us to move our weight farther forward without feeling as if we were going to high-side if it all went south - much like Gee's description of why he liked the updated geometry. The balance is there as well, especially on loose over hard-pack ground that leaves many bikes searching for traction as one end of the machine gives away before the other - likely an attribute of the Fury's 1231mm/48.4'' overall length and balanced feeling rider-weight distribution. Getting the bike sliding over such ground left us far less panicky than on any other bike we've ridden, with the Fury feeling at ease with a bit of sideways action when it was called for. That stability makes for some seriously fun moments on the trail - squaring off corners with long counter steer slides may not be the fastest way down a trail, but it sure is a hell of a lot of fun aboard the GT.

Quick left to right direction changes didn't take a lot of effort, so long as some momentum was on tap, and we would have guessed that the bike's head angle was slightly steeper than its 63° advertised figure. We mean that last point in a good way, though, because the Fury also manages to remain incredibly composed on the steepest, hairiest of sections. The best of both worlds? It looks to be so. Confidence is the name of the game when it comes to going fast on a downhill track, and we had it in spades when aboard the GT.

| The GT's rangy cockpit had us feeling as if it was the first downhill bike that has fit us properly. This view was only cemented by back to back laps on machines with more conventional geometry numbers, with the Fury's roomy front end making those other bikes feel a touch awkward. |

As you might expect, there are drawbacks to the relatively long wheelbase, namely how the bike behaves when speeds fall into the single digits and the corners get ultra-tight. Sure, this could be said of most of the downhill bikes on the market, but the Fury certainly punishes a rider who doesn't carry momentum when speed is the answer. This is obviously not a problem for the Atherton siblings, but putting a real-world, average rider on the GT and asking him or her to thread the gauntlet through turns that ask for lock-to-lock steering won't result in anything pretty. This fact would be a deal breaker for anything but a true downhill race bike, but it can be pardoned given the Fury's intentions. We also continually struggled to bring the front of the bike up in situations that required a manual, with the GT asking its rider to use more body English to do so than other bikes require. It took four full days at Whistler before we could manual the bike with any amount of confidence.

Suspension: With 220mm of travel and a revised version of GT's Independent Drivetrain, there were many questions to answer about how the Fury would perform on the hill. Would the bike pedal as well as its predecessor, a machine that was renowned for its acceleration? With 20mm more travel than the majority of other downhill bikes on the market, would its suspension simply feel too deep and forgiving? Would wearing the latest One Industries gear and a garage-painted Red Bull helmet while aboard the Fury at Whistler allow us to channel any of Gee's skills? Okay, that last one is a definite no, but the rest deserved looking into.

The Fury offers a deep feel that you'd expect given how much travel it has, even relative to bikes with just 20mm less suspension on hand. That, along with its long wheelbase, allows the big GT to provide a supremely confident ride on serious terrain, especially on hard, medium sized impacts that litter a proper downhill track. It simply always felt as if the bike's Independent Drivetrain suspension had loads of capability at its disposal, with a bottomless and controlled feel to it. And while we began the test with the bike's FOX DHX RC4 shock's blue bottom out adjuster turned half way in, we quickly realized that that wasn't needed, with the design offering more than enough ramp-up for our expert-level skills. We managed to feel only a single hard bottoming moment with the said adjuster turned completely out and the pressure set low, and this came only when coming up so short on a rock to rock gap that we expected to get thrown over the front of the bike. We're relatively sure that making the same mistake on a number of other DH bikes would have seen us get pitched off like we deserved to, but the Fury didn't so much as give us a hint of coming to a stop.

The bike's mid-stroke offers a quite a supportive feel that doesn't leave you wondering where it's sitting in its travel, and we'd go so far as to describe it as lively, not a sensation that we were expecting to feel. In the same breath, the rear wheel gets out of the way in a hurry on chunky terrain with as little fuss as possible. GT's Etienne Warnery, one of the main minds behind the new design, told us that the floating bottom bracket unit moves back roughly 10mm as the bike goes through its travel, and we have to admit to not being able to feel that movement when in action. That's not to say that no one out there will be able to pick it up, just that it is a pretty small amount given that it is happening while the rider is busy concentrating on what is coming up next on the trail. There was also no perceptible firming up when standing, a foible that some riders of the previous design sometimes mentioned.

How well do you expect a downhill bike to pedal? How about one with 220mm of travel? While we admit that previous trail time on GT's Independent Drivetrain had us expecting class-leading pedalling performance, we were still astounded by just how much ''jump'' the bike had to it when putting some muscle into the pedals. We kicked off testing with a modest amount of low-speed compression set on the bike's FOX shock, but found ourselves backing it out even farther as it became clear that the bike didn't require such a crutch. This left the rear end free to deal with the ground under it rather than the squares that we were turning with the pedals. For a bike as big feeling as it is, the Fury's relatively light 36.9lb weight and notably good pedalling gave it quite manageable feeling on tame trails.

The Fury's 220mm travel Independent Drivetrain did have one peculiarity that we weren't able to tune out, with high-speed chatter seeming to be transmitted through the bike much more than we would have expected. Riding the same sections back to back on two other bikes (a Nukeproof Pulse with a Cane Creek Double Barrel, and a Banshee Legend with a Manitou Revox) showed that they did much better at muting such terrain. The sensation was present regardless of if we were standing or sitting, thereby ruling out any firming up of the Fury's Independent Drivetrain when out of the saddle, and no amount of tinkering with the bike's DHX RC4 shock led to any improvement. We have to wonder if the frame's tremendous lateral rigidity played a part, especially when cornering on such terrain.

Pinkbike's take:

| After countless runs on both our home mountain and the hairiest terrain that Whistler has to offer, we are positive that GT has hit a home run with their new Fury. And we're not just talking about the bike being for World Cup-level racers, but also for the everyday competitor who doesn't have any illusions of racing in the pro class. The comparatively long front end and wheelbase felt like home after only a few minutes aboard the bike, and we are certain that it had a positive impact on our riding - we not only felt fast, but also comfortable. It has been a long time since we have been this excited about a new aluminum bike with what is essentially a single pivot suspension layout, but the big GT has shot to the top of our short list of preeminent downhill bikes.- Mike Levy |

www.gtbicycles.com

Author Info:

Must Read This Week

Sign Up for the Pinkbike Newsletter - All the Biggest, Most Interesting Stories in your Inbox

PB Newsletter Signup

The Fury sports a mighty looking swingarm (left), and the bike's axle is clamped in place on both the drive and non-drive side (right).

The Fury sports a mighty looking swingarm (left), and the bike's axle is clamped in place on both the drive and non-drive side (right).

If Beaumont was 2 for 2 it would be the same story for him.

What do you expect

ave you ever actually talked to a sales associate at sportchek? I've worked there before and i was the only person on staff who knew Left from Right

It worked for Gwin, going from 20th to 6th or whatever it was. Perhaps we should all give it a try with a 30mm stem and a bike one size up from the norm.

www.mtb-downhill.net/lorenzo-suding-crash-2014-gt-fury-destroyed

I would pay top dollar for that. And you could save money buy testing something before you paid "over nine thousand" for your next bike.

Whistler is 3000 miles away for me, quite a long way to go to test a bike. Anywhere in the UK a proper test on a demo fleet is not really an option. Maybe you have a quick go on a mate/random rider's one - you know that guy who is 2 stone lighter & six inches shorter than you and has his controls setup all weird. And that's about it, if you're lucky.

No wonder there is so much interest in bike's visual appearance and what the pros are riding. Cos most of us end up buying blind IMO. The only good thing is that at least all the top end bikes are damn good nowadays.

The point of this slightly-more-expensive rental service is that you can go in after a couple runs and switch your bike for another one (if it's available). If you're thinking of throwing down anything up to $10K for a bike, it's worth the money to try a few out first. There's a few missing from their fleet but you can get those from other stores relatively cheaply and if you do end up buying they'll take the rental cost off the bike.

One of the other best ways to try out multiple bikes is during Crankworx. Most of the major manufs have a demo fleet and you can take them for a few laps for free (leaving a credit card) but it's fekkin busy during that week so a) getting a bike is hard, and then b) doing fast laps on trails is difficult with the crowds.

You gotta have dialed sticker placement to go fast...everybody knows that.

Geometry and well damped suspension is what counts.

Axle path? Wheel has to go up, to make away for the obstacle - that movement is hindered by the shock so the input it gets through linkage design and how it reacts to it through damping is far more important. Even geometry and the way it influences riders balance, probably has more to do with that.

Also no axle path in terms of how much momentum the bike looses on hsc hits is more important than leverage curve. The reason why not everyone goes very rearward is there are other qualities in the bike than being super stable over the rough. Remember that axle path also has influence how the bike reacts in corners and usually rearward bikes require a different cornering style.

@spaced: not really.

Apart from the messy BB - this bike is a blatant chinese ripoff of a Foes. The rattle over obstacles has probably to do with the rear shock linkage standing at 2 clock instead 4 clock.

Also can you please coment on what bikes have sub 241mm shocks? You claim so many of them have. Of the popular brands I know of 3.

Foes has 266mm shocklength or 8.3/210 travel. More if you want. So yes bikes with 241 or less are a thing of the past. Riding too high springrates degrades riding. 140lb rider weight equals 200lb spring. That is smooth.

And Slayde is right; I fell for the marketing there! It really isn't that high for a pivot location! Must stop reading things written by marketing before discuss a bike!

As for foes and 260mm shock. LOL. 241 is a thing of the past? Then why so many companies go for it? Riding to low leverage ratio means shock friction is a bigger problem, it also means it's harder to find proper springs for lighter riders and the springs need to be made more precisely as many steel springs have 15-20lbs margin of error, sometimes more. Please stop commenting when you have no clue about suspension and all you want to do is hype up your foes. At least try to understand why it's a good bike.

it's just people disagreeing with you. Don't take it personally.

Foes BB is adjustable. Mine is low. Reach - depends which framesize you compare, more reach - less pressure on the front wheel. Chainstay is long on both frames - compared to "short" on older frames. Moot.

Head angle and geometry on Foes is adjustable. Not on GT. Mine is set low, flat and long. Different pushrods, shock receptables. Good stuff.

Yep, 241 is short, longer is better. Plenty of springs for 260 shock available. Most springs are within 10% error marging. Fine with me.

Shockfriction higher when using a 260? WTF are you talking about? Friction and stiction is the same on a 241 or 260. Look ahead. Most frames on the market now are at least four years old and it shows. Foes and Scott already use 267mm. See the trend?

I dont hype my bike. Concept, engineering and execution is very advanced and that is why I ride one. And you need to control your jealousy thing, b&7%!

Also no 241 is not short. And 10% margin of error on a 200lbs spring is 20lb. Given the fact that on a low leverage bike you need 25lb increments for different weight a spring that is 20lb may be for someone who is 10kg heavier. Fine by you?

As for friction and stiction yes they are the same but if you have lower leverage ratio it is harder to OVERCOME friction. You are 46 yet you don't understand the basic phisics of a lever. They teach that to 14 year olds.

As for seeing the Trend. Foes has been using the same shock for years, once a few years you have a 267mm shocked frame. It's no trend. 267mm shocks have been available for quite some time and they haven't been adopted. Trek session 10, Morewood makulu have used the same sized shock quite some time ago. Trek went back to a shorter shock. I see no trend. Unless more frame designers adopt it it's no trend. 2 frames don't make a trend. Also mfg's won't go for 2.3 leverage ratio because as mentioned before (and as many of them have also mentioned) it has many drawbacks.

What is wrong that I'm writing? With a lower leverage you need more force on the wheel to have the same force act on the shock. Of course spring rates and damping are also important but that can be setup for a given leverage ratio. Friction in dampers can't be. Sorry I'm im not expressing myself clearly. I'm at work and after 5h of sleep.

Zen hmmmmmmmm

Anyways, I've never ridden a Fury so can't defend it, but it seems pretty clear that GT doesn't get a fair shake in the comments section here.

The more Dorel makes the more its shareholders make - and these guys would be seen dead on Dorel brand - they ride custom boutique bikes...So yes it is about class. And marxism is analysis of capitalism. Both are tools of understanding. You lack understanding and that is why you will ride Dorelbikes forever - so its about class again...hm.. not understanding capitalism makes you a bad capitalist and that is worse than beeing a communist?

Your racers ride whatever from whoever and promote anything. They get paid do that. It has no intrinsic quality value and is about retaining marketshare. Big brands dont R&D. They set a pricepoint and spec and invite offers. Cheapest gets it. It is altogether different with trendsetting small local manufacturers. Few of them left and worth supporting. Some have very good thinking going. For this I am willing to pay. I want value.

GT hydroformed parts dont look like they are from the better suppliers. Dorel probably sources them from some lowend sweatshop. Also the welding looks a bit iffy - many weldstops where there shouldn`t.

I always trust handmade bikes made in my area more but as bassnotesteve steve said, a worldcup winner can't be as bad as wakaba says...

But in this example, Patrick9-32 is (presumably) right.

I guess you never went to college / university and had to write a paper ?

I've also been waiting for a manufacturer to come out and say "Y'know what? We don't need a carbon frame."

To this end I'm dropping one of the brands in my shop in favour of GT. Always liked their commitment to racing of all types (apart from road).

Hate GT all you want but it sounds like they are listening to what's being said and finally moving with the times, not all riders can't all afford 8K plus bikes!

Does it matter that they make cheaper bikes that allow more people to go out and have fun?

As for testing bikes will continue,

I simply dont get what the issue is. What does high-speed chatter mean?

Also, something that no one has ever addressed with floating BB is that it negates nearly all the advantages of a high pivot point! Most of the mass is carried into the frame from the feet/pedals, and this moves rearward slightly as the rear wheel encounters a bump, meaning that most of the rider moves slightly rearward as well.

I really want to test ride this bike! If it rides so well without a linkage actuated shock, why mess with complicated suspension designs? The single pivot heckler I used to ride would bottom out too easy with a coil, but here they say bottoming out wasn't an issue. I wonder if its a custom tuned fox in the back. Wouldn't an air shock work great on this design and emulate a more progressive curve?

The new fury is more progressive than the previous one... but actually it's not very progressive.

As for testing bikes when I brought my GT fury I wanted to test ride all the top bikes to see which I liked most I worked it out it would of cost me around £450 and a loss of £300 when I chose my bike as they didn't have one shop that did all. That is a joke territories mean shit we go to the shop we like just because I have a GT I do t take it to a GT shop I take it to the shop I deal with simple. Sorry rant over

As for the new GT drop outs look shit bike looks awsome and the athertons are awsome good on them.

Mike- What were the heights of the riders that tested this bike? I watched the video of the team and Rachel also is riding a large for some races. Noticed a lot of people were mentioning that GT had reverted to aluminium for this frame but the article does say that this is paving the way for the carbon version once the geometry is dialled. Maybe 2015 we will see a 650b carbon fury. Yes please (funds permitting)

After 2 weeks aboard the new GT, I have to say it is an incredibly single-minded bike. I have to reinforce that the big GT most certainly IS a handful when it gets tight. Picking tight lines in between roots or squaring off turns at lower speeds is an absolute no-go... this bike just wants to pick the straightest line possible in those situations, It takes some serious muscle to get this bike to turn. I'm sure the 650b wheelseize isn't doing much to help matters at low speed.

However, once you get this bike up to medium and high speeds, it really comes alive, with a surprisingly poppy nature. It really is like flicking a light switch... this bike goes from big dull unweildy beast to a pin-sharp weapon. The high speed handling really is great... you're stretched out and it just encourages you to attack everything in your path. The jumping is also very predictable and it's actually incredibly agile in the air.

I have to say that for the DH tracks I have so far ridden in the UK... this bike is 50% amazing and 50% complete disaster. Make sure if you get yourselves one of these, that you have the right terrain to ride it on because it sure as hell isn't going to suit everyone. That said, I can't wait to get the bike out to whistler in July so that it can be in it's element all week long :-)

"also for the everyday competitor who doesn't have any illusions of racing in the pro class"

How do those two statements sit together? Also, doesn't putting the BB on the swingarm massively increase the unsprung mass?

So :

你喝醉了吗?